<title id=“p015r_a1”>Damask Cloth</title>

<ab id=“p015r_b1”>You can make damask cloth of two different colours and imitate embroidery without adding anything else to it, as follows. Once it is is dyed yellow, pounce onto it such a pattern as will please you. Then you will sew some string

or a bigger cord loosely onto the pattern and throw it into a dye of woad or pastel and it will become green, except that which is beneath the string, which will remain yellow because the green dye will not have penetrated there. And you can do the

same with other colours and, instead of string or cord, add some pieces of poor quality cloth cut in Moorish shapes on top of the first colour. In that manner, you will have cheap embroidery.</ab>

discussion with Jenny

cord: cord

string: packthread

faulfiler;;sewing provisionally

an ornament realized with a needle on a piece of cloth

it makes cloth that looks like damask, of two different colors, imitate the (damask) pattern (or ornament or design--broderie) without adding anything else

damasse: pattern in the fashion of damask

damas: damask!(cotgrave)

loosely: provisionally

except that which is beneath the sting, which remains yellow green dy

COMMENTS:

WHAT IS END USE OF THIS EMBROIDERY?

FUGITIVE HISTORY OF YELLOW--PAY ATTENTION TO THIS.

--> So I talked to my friend, who studies the history of Korean dyeing and is a practitioner of traditional(natural) dyeing herself. History of yellow is more or less the same in Korea and she thinks it possibly results from the properties of yellow. A color

that we see in a plant is actually comprised of several different colors. For instance, if we are to get a red dye out of a red plant, we will have to get several different colors prior to getting true red. And yellow is likely to be the first color one can get

from the plant (and actually many other plants with different colors). Yellow exists in almost every plant, is easy to obtain, and, for this reason, disappears easily . I will keep searching information on yellow--both historical and chemical.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT OF WOAD.

--> I've found quite a useful website on woad: http://www.woad.org.uk/

ALEXIS HAGEDORN, DIRECTOR OF CONSERVATION LAB, BUTLER LIBRARY

PASCAL JULIEN, UNIV. OF TOULOUSE, SEND WOAD RECIPE TO HIM AND SEE IF HE KNOWS ANYONE WHO WORKS ON WOAD.

--> I emailed him but have not heard back yet.

[Annotation Plans]

Materials

Fabrics: cotton, silk, and linen (1 or 2 yards/ each?), washing soda, detergent for cotton and silk.

Dyes of yellow: saffron and/or dried weld, quicklime

Dyes of woad or pastel: we have three options: woad leaves, woad balls (semi-processed woad leaves), and woad extracts

Paper and powder for pouncing

String(or cord) and coarse cloth for making patterns.

Tools

A 10 liter stainless steel pot, a stainless steel spoon, rubber gloves.

Schedule

- Week of Nov 9: Scouring

- Week of Nov 16: Dyeing yellow and patterning

- Week of Nov 23: Dyeing blue

Procedure

1. Prepare fabrics (Scouring)

As suggested by Marjolijn, we will test on various materials (cotton, silk, linen) to see how they can be dyed differently.

We will first scour fabrics to get rid of oils and starches added in the course of manufacture.

For sourcing fabrics and cleaning materials I find this site useful:

- http://www.dharmatrading.com/fabric/cotton/cotton-fabrics.html

- Fabric shops near FIT are also useful.

For modern manuals, I primarily relied on these sources:

- http://www.wildcolours.co.uk/html/cotton.html#how-to-scour-cotton

- Liles, J. N. The Art and Craft of Natural Dyeing: Traditional REcipes for Modern Use

Protocol for cotton and linen

- Weigh fabrics prior to washing

- Fill a large nonreactive vessel with water (2 quarts per ounce of fabrics)

- Add 1 teaspoon detergent per gallon of water and 2 teaspoons of washing soda per ounce of cotton.

- Add fabrics and simmer for a minimum of 2 hours. The longer, the better (3-4 hours)

- Remove the pot from the heat and let it cool down. Check how dirty the water looks. It is usually yellow-brown.

- Rinse 2 or 3 times. If the scouring water is brown or grey, repeat the process

- Dry and Weigh

Protocol for silk

- Weigh silk

- Use 8 gallons of hot tap water per pound of silk

- Add 2 or 3 tablespoons of silk washing liquid (I am going to use Woolite)

- Simmer the silk for 30 to 60 minutes

- Rinse thoroughly

- Dry and Weigh

- If the silk is already degummed we won't have to go through this process. We only have to wash it with silk washing detergent

2. Dye yellow

The recipe does not mention specific materials to get yellow. In the BnF, several plants including saffron (038r ,020r, 029v, 041v), weld (010r), lapathium acutum maius(040r), and marigold (038r) are discussed to get yellow colors. But specific procedures to extract dyes are not provided.

From Jo Kirby's book, I've learned that both saffron and weld were widely used to dye fabrics, so we've decided to test on these two materials relying on other related recipes.

The Art Conservation Department at the U of Delaware offers useful information on historical dyestuffs (http://www.artcons.udel.edu/public-outreach/historic-art-materials/yellow-dyestuffs). It says saffron "has been prized for centuries as a food

additive as well as its ability to produce a red-yellow dye." For weld, it says "[h]arvested from the Reseda Luteola plant native to Europe, Britain, and the Mediterranean, this dyestuff produces an intense yellow when combined with an alum mordant.

Copper mordants can also yield a green color and iron, a green-yellow. Weld has been used since ancient times and is often combined with other dyestuffs such as woad and indigo to create a range of greens heading towards blue. It has also been

used as an ink (dissolved in alcohol) and can be found in medieval paintings and manuscripts."

- According to the BnF, saffron seems to be used for coating as well.

2-1. First Option: Saffron

Related Recipes: ON THE CHARACTER OF A YELLOW CALLED SAFFRON. CHAPTER XLVIIII (from Cennini)

A color which is made from a herb called saffron is yellow. You should put it on a linen cloth, over a hot stone or brick. Then take half a goblet or glass full of good strong lye. Put this saffron in it; work it up on a slab. This makes a fine color for

dyeing linen or cloth. It is good on parchment. And see that is is not exposed to the air, for it soon loses its color. And if you want to make the Most perfect grass color imaginable, take a little verdigris and some saffron that is, of the three parts let

one be saffron; and it comes out the most perfect grass-green imaginable, tempered with a little size, as I will show you later.

Historical Context of Saffron (from Merrifield)

(pg. clxv) Saffron, zafferano, the crocus of the middle ages, is produced from the flowers of the crocus. Peter de S. Audemar informs us that saffron was produced in France in his time; but he says the French saffron was not good; he mentions that

this drug was imported from Spain and Italy, and that the best kind was brought from Sicily, and was called corsicos. The plant is cultivated extensively in England in the neighbourhood of Saffron-Walden, and the name of the place is derived from

this circumstance...

Historical Context of Saffron (from BnF)

<id>p038r_2</id>

<head><m>Saffron</m></head>

<ab>It is imitated and increased with half dried marigold leaves, twisted like a thread, and dried in the hottest sun, and this is mixed, and the aforementioned marigold even adds some dye.</ab>

Questions

- What's the use of lye in Cennini's recipe?

Does it serve as a mordant agent? According to Jo Kirby, saffron is one of the plants that do not require mordants. Then what is the purpose of lye?

Lye was widely used to bleach linen. Was it used for that purpose in this recipe?

http://www.ukessays.com/essays/sciences/looking-at-the-history-of-bleaching-science-essay.php

- Do we not boil the lye? We will get to add some heat any way by following the recipe. We will see how it goes.

- The recipe does not specify quantity info. I will use saffron in the amount of 4 % of fabrics. See

A review of the chemistry and uses of crocins and crocetin, the carotenoid natural dyes in saffron, with particular emphasis on applications as colorants including their use as biological stains

Protocol 1

- Scour fabrics and dry (we won't mordant them)

- Prepare 2 1000 ml beakers and half fill each with wood ash lye

- Heat a steel plate (measure the time and temperature)

- Place a linen cloth on the plate

- Weigh out saffron (0.07 g * 2) and put it on the linen (measure the time)

- Soak the saffron in the lye, and leave it for a while (measure the time)

- When the color turns yellow, take out the saffron.

- Immerse fabrics for 30 minutes (or 1 hour depending on the progress).

- Remove, squeeze out, cool, rinse, and dry

Protocol 2 (in case protocol 1 fails)

- Prepare 2 1000 ml beakers and half fill them with wood ash lye.

- Simmer until the color is gone

- Dye fabrics for the same amount of time

- Remove, squeeze out, cool, rinse, and dry

Protocol to make lye

- It won't be feasible to make lye in a traditional method in the lab. I will make it using quicklime

- Fill half two 1000 ml beakers (500ml water *2)

- Add 60g of quicklime each (50g *2)

- Add 60g of washing soda each (50g *2)

- Boil for 20 minutes.

- When cold, pour off the liquid part.

- I consulted this site:

http://www.countryfarm-lifestyles.com/make-lye.html#.VkK30rerSUk

Modern manual for dyeing with saffron (for reference)

Cennini does not provide detailed quantity information.

- Prepare dried flower stigmas (whole)

- Weigh out saffron (1 g for 2 gallons of water). Simmer until all the color is gone from the stigmas.

- Cool the dyebath to about 130 to 140 F, then add pre-scoured, damp fabrics.

- Dye at 130 to 150 F for 20 to 30 minutes.

- Remove, squeeze out, cool, rinse, and dry.

2-2. Second Option: Weld

I have not found any recipes for dyeing fabrics with weld. We will have to apply saffron recipes and/or refer to modern recipes of weld.

Protocol

Modern manual for dyeing with weld (for reference)

- Soak dried weld in water overnight (25- 50 g dried weld for 5 liters water for 50 g mordanted fibers)

Adding chalk (calcium carbonate) can make stronger yellows

- Simmer it for about an hour; do not boil.

- Let the dye cool and strain.

- Add fabrics and leave them overnight. (we can re-use the strained weld)

- Wash the fabrics in cold water

Modern manual for mordanting cotton/linen (for reference)

- Soak 100 grams of scoured cotton in warm water for at least two hours.

- Use no more 100 grams of fabric in a 10 liter pot.

- Half fill the pot with hot tap water.

- Weigh out 7- 10 g of aluminium acetate, and dissolve it in a small container with boiling water. Then add it to the pot and stir.

Aluminium acetate is a very fine powder. Use a mask when weighing it.

- Add the fabric and squeeze it a few times (Do wear gloves!)

- Leave overnight. Wring and dry. Wait until the vinegar small disappears, which can take up to 4 days.

- When ready to dye, rinse it.

Modern manual for mordanting silk (for reference)

- Weigh alum (6% of the weight of dry silk)

- Put the alum in small container and pour boiling water into the container. Stir it until dissolved.

- Fill the pot 3/4 full with hot tap water, add dissolved alum and stir.

- Add the warm, wet silk, and leave it for 48 hours. Don't add any heat and stir gently and occasionally.

- After 48 hours, take the silk out and leave it to dry. Keep it for at least a week before washing and dyeing.

3. Patterns

3-1. First Method: Pounce a pattern onto the yellow cloth and and sew it.

We are going to sew Moorish shapes (scroll down to see the shapes)

Get paper and powder for pouncing.

Then need to source strings or cords--but wouldn't using such coarse materials (not threads) leave big holes on the cloth? This makes me doubt if the author practiced it himself.

3-2. Second Method: Add pieces of cloth cut in Moorish shapes

What are the Moorish shapes? (scroll down to see them)

How do we add it on the yellow cloth? Will have to sew.

4. Dye Blue (and thus Green)

It will be helpful to test woad on plain cloth as well to see the difference.

So far we've found a recipe to get blue, maybe the practitioner expects the combination of blue and yellow to make green in the area where both dyes are used

Related Recipes for Woad

1) From BnF

<id>p039r_2</id>

<head><m>Dyers woad</m></head>

<ab>It is grown in <pl>Auragnes</pl> where the soil is so fertile that if you grew wheat there

every year, it would fall over from the kernels being too full. This is why <m>dyers woad</m>

and wheat are cultivated alternately. For cultivating </m>dyers woad</m>, the soil is ploughed

with <m>iron</m> shovels like those of gardeners. Then with rakes, clods of earth are broken

up and tilled as for the sowing of some vegetable gardens. It is usually sowed on Saint

Anthony’s day in January. Eight harvests can be made. The first ones are the best. The best of

Auragne’s <m>dyers woad</m> is the one from <pl>Carmail</pl> and the one from

<pl>Auraigne</pl>. And sometimes the <m>dyers woad</m> is good in one field and worthless

in another that is closeby. The quality of the <m>dyers woad</m> can be recognized when you

put it in your mouth and it tastes like vinegar, or when you crumble and break it, there are silver

or golden moldlike veins. It is pressed in the dyers’ cistern, and to fill a cistern, six bales are

needed. Several <m>wool</m> flocks are kept there. And if it produces 15 dyings, it is said to

be worth 15 florins, if it produces 20 dyings, 20 florins. The good kind will dye up to 30 times and

usually up to 25 or 26.</ab>

</div>

But this one does not really tell us about specific processes.

2) Recipes in German(?) from the Database on Colour Practice and Knowledge: https://arb.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/node/81566

3) Translated from the French manuscript in 1816 and provides a detailed account on how to extract indigo from woad (and a lot of useful information on the historical context of woad). Lasteyrie, C. de (Charles). A treatise on the culture, preparation,

history, and analysis of pastel, or woad; the different methods of extracting the coloring matter, and the manner of using it, and indigo, in dying. To which is added, information upon the art of extracting indigo, from the leaves of pastel ... Translated from the French, by

H.A.S. Dearborn. Boston, 1816.

(http://find.galegroup.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/mome/eToc.do?inPS=true&prodId=MOME&userGroupName=columbiau&tabID=T001&searchId=R1&searchType=AdvancedSearchForm&contentSet=MOMEArticles¤tPosition=1&showLOI=}&docId=U3603328125&docLevel=FASCIMILE&workSubLevel=ETOC&workId=19010212200800&action=DO_BROWSE_ETOC&&collectionId=ocm16893196&relevancePageBatch=U103328021&totalCount=1&sort=DateAscend&doDirectDocNumSearch=false)

Related Recipes for Making Green out of Blue and Yellow (from BnF)

p032v_1Mat Makers

Two kinds are made in Toulouse, one to cover rooms’ walls which are finely woven, almost like straw hats worn by villagers, and are made in long rolls, some 10 straws wide, others 13. And they work on them mainly in summer and winter. Then when they prepare it they sew it, but beforehand they dye it in usually three colours: green, red and sometimes purple. The green one is made with only a pastel tincture since green is made from yellow and blue, so the pastel dyes the dark yellow straw. It becomes bright green. For red they use some alum and brazil wood, for purple they use pastel and some coperous which darkens blue with its black tincture.

p037_2Glass-maker Some do not lay gris d’escaille on the glass to work on it, but trace straight on the glass with noir à huile. However, it is important that the wood be degreased, because if it has even a little grease [on it], the color will not take at all. And even, if the working glassmaker has a stink from his nose or his mouth, and he breathes on the glass, the color will not take on it. Those who came up with the invention of working in small works of softened enamels use only azure enamel, which is blue, and esmail colombin, which is the color of purple, which they soften with rocks or lead glass. As for yellow, they make it from silver, red from sanguine, as is said elsewhere, black and gray and shadows from scale black, either strong or weak, carnation from light sanguine. Green is made first from yellow, then they overlay azure enamel, either strong or weak, depending on whether they want to make it bright or dark.

Experiment PlanAs for sourcing woad, we have three options: woad leaves, woad balls, and extracts.

1) Woad leaves: It would be ideal to begin with extracting indigo from freshly harvested woad leaves, but the thing is that it is too late to get good-quality leaves (best-quality leaves are generally harvested in summer). I talked to a couple of experts(practitioner) of woad dyeing in the US and UK, and both of them are negative about this idea, although the UK expert said it might be worth trying given that this fall has been pretty warm. But again, it seems that there's no woad growers around NYC or even in the US. I talked to the dealers that Cindy mentioned, but they rely on imported woad extracts (one from France).

2) Woad balls: If we have to jettison the woad leaves option, this might be the best. It is a kind of semi-processed woad leaves, and I've found one supplier online:https://www.etsy.com/listing/232697812/woad-ball?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=shopping_us_a-craft_supplies_and_tools-fiber_and_textile_art_supplies-other&utm_custom1=1e7daaa6-48c2-4560-9c1c-b37b96415c15&gclid=CjwKEAiA3_axBRD5qKDc__XdqQ0SJAC6lecAsLD3xPJpD9egKFvdXRiXvnMKOc4iprRgr7T2xXsQCRoCl8jw_wcB

The American woad expert said that woad balls might be a good option if we can source one. The product in the link is imported from England.

It seems that making woad balls was a common practice to circulate woad at that time. It was briefly mentioned in a document that had noting to do with dyeing: http://eebo.chadwyck.com.ezproxy.cul.columbia.edu/search/fulltext?ACTION=ByID&ID=D40000998954330418&SOURCE=var_spell.cfg&DISPLAY=AUTHOR&WARN=N&FILE=../session/1446870243_17998

3) Extracts: There are abundant suppliers so we should not worry about sourcing this. I confirmed with Kremer that their woad extracts are intended for dyeing, but Cindy was told differently! Anyway they don't have stock right now.I know that the sourcing plan needs to be finalized by this Monday but I would like to finalize it with other faculty members that day and then proceed (if we go for balls or extracts, or both?).The American expert cautioned that blue color one can get from woad leaves can be very different from that of extracts. Extracts are much stronger. While the BnF recipe does not specify the process for extracting, the treatise above does.I am not sure if it is because the method for circulating woad has been changed or simply the BnF did not talk about extraction.

4) Dyeing: Whatever source we use, we won't be able to follow the traditional fermentation method, which needs to be done in summer requiring a space between 35 C and 43 C. We will have to rely on a chemical method like this:

http://www.woad.org.uk/html/chemical.html

[General Questions to Ask]

1. What is "damask cloth"?

Dictionary of Textiles by Louis Harmuth in 1915:

1) "originally a rich silk fabric ornamented with colored figured often in gold or silver; 2) an all-worsted twilled fabric made in England in the 18th century; 3) the true or double or reversible damask is woven both the ground and the large floral

Jacquard patterns in eight-leaf satin and the single damask in five-leaf satin weave. Single damask is also made with figures, not in satin but plain or twill weave. Usually made of cotton or linen and used on the table."

Fairchild's Dictionary of Textiles by Stephen S. Marks in 1959:

"Originally a rich silk fabric with woven floral designs in China and introduced into Europe through Damascus, from which it derived its name...Damask has been made for centuries and is one of the oldest and most popular staple cloths.

Used for upholstery and draperies, table cloths, napkins, bedspreads, face towels, evening wear, etc."

http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=wu.89043757574;view=1up;seq=181

101 Fabrics: Analyses and Textile Dictionary by J. J.Pizzuto in 1952:

" 1) Table Linen: A fabric with an elaborate Jacquard design. It has a warp face satin weave for the pattern and a filling face weave for the ground. For table linen, single damask is made with a five harness satin weave, double damask

with an eight harness satin weave: usually made of linen but may be made of cotton or rayon. 2) Drapery or Upholstery: Elaborate fabric in satin or satin or twill weave combination; woven in dobby or Jacquard patterns.

The fabric is made with long floats which form the pattern. Fabrics are soft lustrous, and drape well. Cotton, silk, or rayon may be used. The yarns are usually single in the warp, and single, plied, or novelty in the filling. 3) Ticking: Elaborately

designed, Jacquard woven fabric with warp and filling satin weave floats of contrasting colors. This fabric is used for mattresses and may be made of cotton , or rayon and cotton"

http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015021215481;view=1up;seq=134

From the sources above, damask generally means patterned woven fabrics intended for interior decoration.

But these sources were all published in the early 20th century. Further research on the history of damask in the 16th century will be required.

Meanwhile, I searched "damask" "made between 1300-1700" on the website of V&A museum.

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/search/?listing_type=list&offset=0&limit=45&narrow=1&extrasearch=&q=damask&quality=0&objectnamesearch=&placesearch=&after=1300&after-adbc=AD&before=1700&before-adbc=AD&namesearch=&materialsearch=&mnsearch=&locationsearch=

As described in the dictionary definitions above, most searched items were patterned, woven fabrics made of silk or linen. There was no cotton damask.

Unlike Italy, where a good number of damask fabrics made before 1600 were searched, most damask items from France were produced after 1600. I am not sure whether this could tell us something about weaving technology in France and the status

of damask in its fabric market at that time.

On the website I also found a concise definition of damask:

"a woven material whose effect depends on the differing play of light on its pattern surfaces, which alternate between the smooth face and the contrasting reverse of satin weave."

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O82549/dolls-undress-gown-unknown/

In other words, unlike other types of weaving that make patterns using different colors of threads for warp and weft, damask create patterns using identical colors for warp and weft. Its patterns are created by difference in luster rather than color.

The this definition is not used consistently on the V&A website.

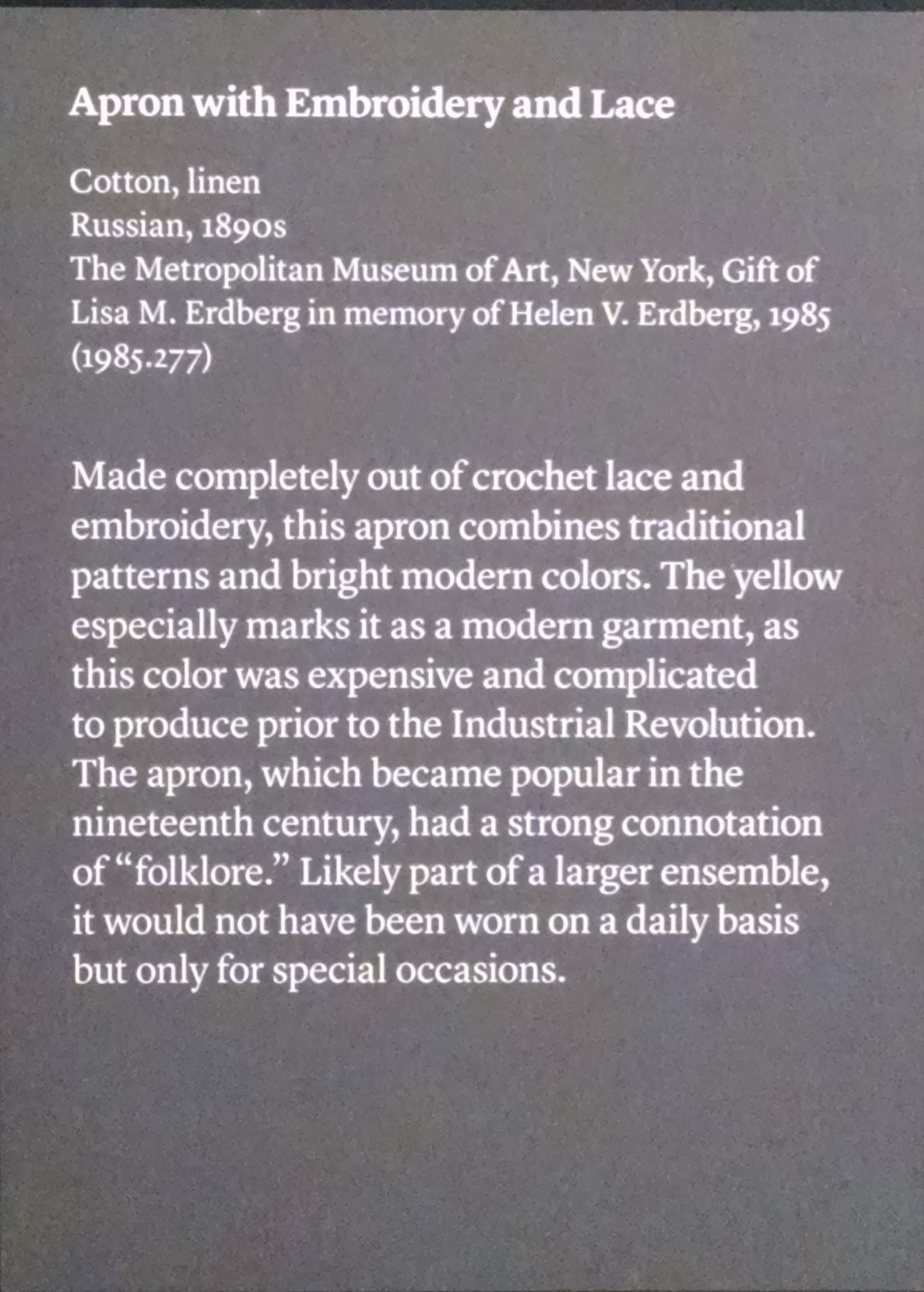

Below is silk damask made in Italy between 1600-1650. Intended for furnishing fabric

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O225682/furnishing-fabric-unknown/

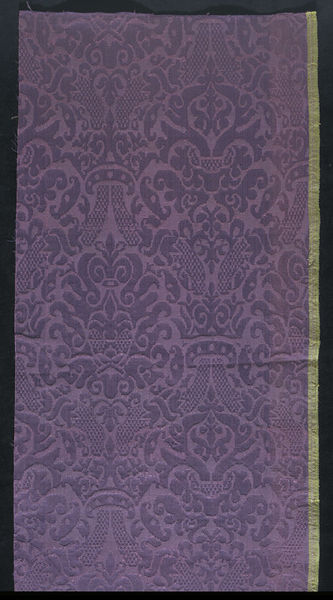

Linen damask napkin made in Flanders between 1570-1600. The annotation says the highest quality linen was woven in the Southern Netherlands.

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O101377/napkin-unknown/

So are these what the author meant by "drap damasse (damask cloth)"?

I looked up the term in several dictionaries.

Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues by Randle Cotgrave in 1611.

"Drap" means cloth; woolen cloth; broad cloth

It did not have "damasse"

The Royal Dictionary. French and English. English and French by Abel Boyer in 1729.

"Drap" meant woolen cloth.

Again, there was no "damasse"

I've found "damasse" in Dictionary of Textiles by Louis Harmuth in 1915.

It means: 1) French shawl, made with combed wool warp and filling with large flower designs; 2) French for fabrics having both the ground and the large patterns woven in satin weave but of various colored or lustered yarn; 3) in French general term

for fabrics woven on a Jacquard loom.

The second definition of "damasse" is close to the definitions of damask discussed above.

In summary, it can be said that "drap damasse (damask cloth)" is woven, patterned fabric. Extant artifacts tell us that it is mostly made of linen and silk but as seen from the definition of "drap" there is also a possibility of woolen cloth.

2. What is "Moorish Shape"?

I searched "moresque" "between 1350-1750" "made by damask technique" on the V&A website, which yielded only one result:

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O264602/woven-silk-unknown/

It was woven using more than three colors, which contradicts the site's definition of damask.

I again searched "moresque" "between 1350-1750" "made in France."

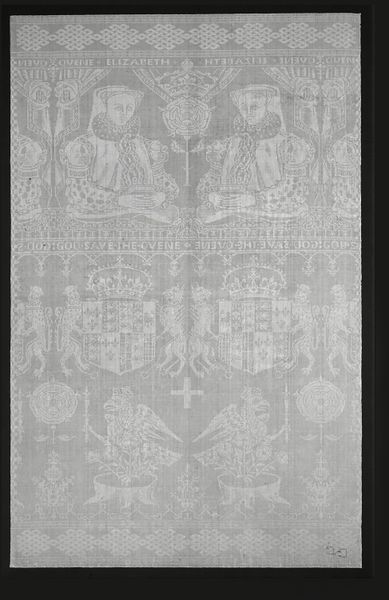

It did not show any textile items but instead numerous prints for ornament such as this:

http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O755213/print-anonymous-engraver/

The annotation says it was "a design for goldsmith's ornament containing a Moresque design," made in France between 1510-1551.

It tells us that Moresque designs were circulated among French artisans for making various sorts of crafts.

Another print. http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O755212/print-anonymous-engraver/

For our experiment we could possible use one of these patterns.

3. The whole process actually does not make sense to me, because the woad (or pastel) will ultimately penetrate into the patterned part--unlike tie-dye, loosely sewed strings/cords and a piece of cloth simply attached to the other cloth would not resist it. We will see how it goes.

[Principal Recipe 2: Green]

Nov. 9, 2015 email to Professor Smith

After talking to Jenny and Naomi, I'm going to focus on the yellow pigments used to modify verdigris in the green leafs recipe: yellow ochre, massicot (yellow lead), and scudegrun (from two separate recipes in the manuscript based on weld and broom flower). We will also be testing weld and broom flower for the Damask Cloth dyes. On this point, we're interested in how the author/practitioner might have experimented with processing a certain type of plant in different ways to use in different mediums. In general, we're considering the qualities of different types of yellow and for the scudegrun recipes, we're interested in how changing variables in the process of making the yellow lakes (such as precipitating on to ceruse instead of chalk) might result in a pigment with different aesthetic qualities.

[On weld and broom flower: weld is mentioned in Merrifield and other contemporaneous sources as a source for pigment making. The Pigment Glossary defines dyer's broom as "Genista tinctoria L., the source of a yellow dye, obtained from all parts of the plant except the roots. The dye was used in the preparation of rather acid lemon to brownish-yellow lake pigments, very similar to those made from weld (q.v.). The plant was found all over Europe." The French in the scudegrun recipe, f. 63v_3, uses the term "fleur de genest" for broom flower and the process for making this pigment is very similar to the process for the weld-based pigment, f. 20r_2]

I would like to request from Kremer:

1. French Yellow Ochre Sahara, 100g

2. Burgundy Yellow Ochre, 50 g

From the manuscript, the author does not indicate the source of his yellow ochre and I haven't found any references to yellow ochre in the Toulouse region. The Pigment Glossary (Jo Kirby, et al.) mentions that "although these pigments occur very widely, certain regions, including France and central Italy, were the source of yellow ochres of particularly good colour." Although ochre was traded between regions, the French ochre might be more accessible to the author/practitioner than a foreign import.

3. Massicot (Yellow lead), 100 g*

In a note in Cennini, "massicot [is] a yellow oxide of lead, prepared by roasting white lead...Natural massicot, of volcanic origin, is know; but it is not generally available." In modern pigment compendiums, massicot is consistently defined as a lead-based yellow.

4. Cremnitz White, 100 g*

White lead is used as a substrate onto which the yellow lake in the scudegrun recipes is precipitated, so it would need to be in powder form. I think it could be important to test ceruse because in f. 10r_2, the author/practitioner advises makers to mix the "sap of weld" with "chalk or better yet with ceruse" (croye...ou pour mieulx avecq de la ceruse"), perhaps indicating a notable difference between the chalk and ceruse as precipitants.

Other recipes that mention precipitating onto ceruse include Brussels Manuscript 194 (Merrifield, pg. 786), which instructs makers to "take 1 lb of weld...then take 2 oz. travertine finely ground, or 2 oz. white lead, and half oz. of roche alum ground very fine..." and the Paduan Manuscript (Merrifield, pg. 650) which explains, "Yellow is made with white lead and gialdo santo." In her email, Jenny linked the Essential Vermeer which mentioned precipitating onto white lead and I believe that website's source was the Pigment Compendium which says, "The pigment is produced by strewing the whole dried plant in a weak solution of alum and then precipitating this with the addition of calcium sulfate, eggshell or lead white. Thompson (1960) states that the colour was most beautiful when somewhat opaque but that when precipitated onto eggshells or lead white it produced a very brilliant colour…"

If the white lead is not a viable option, other recipes mention chalk, like in Bnf.640 or eggshells. The Pigment Glossary and the National Gallery both discuss how the yellow lake was precipitated onto a form of calcium carbonate, such as crushed eggshells or chalk. I'm still looking into how the chemical structure of white lead might be similar to chalk or what allows it to serve a similar function in this recipe.

*Note on Safety: I've talked to Katie and Siddhartha about their safety protocol for using minium and looked at the MSDS for massicot and white lead, which have similar warnings and precaution instructions as minium. If we do proceed with using the massicot and white lead, do we set up a separate meeting with Safety Training?

[Annotation Plans]

This recipe is relevant because it pays attention to how colors (primarily green and yellow, as in the damask recipe) are mixed, albeit in a different medium (oil paint) than our principle recipe. It gives detailed instructions on how to make different hues of green, some of which are mixed with yellows which may also be used in making dyes. The recipe is specifically for painting on metal casts, to give the cast plant--for example, marigold flowers, as the author specifies--a more lifelike color.

Merrifield discusses how dyes and pigments can have the same basis or be derived from the same plant through different processing methods.

Merrifield, pg. 7

It is certain that these passages relate to the preparation of transparent colours for painting; but I think that they refer also to the art of dyeing, and to the decoration of wearing apparel. No. 92 is evidently a mordant, and was used both to prepare the cloth to receive the colours, and to bleach certain parts of coloured cloths, by which a regular pattern might be given to them...

Questions

why was white lead used as this if it was so familiar as a colorant?

how is white lead chemical structure similar to chalk? both not very reactive

taxonomy of materials for the author practioner--how he understands white lead and chalk as in the same family

Materials:

oil (unspecified in recipe): linseed? walnut?

vert-de-gris (in lab)

massicot (yellow lead) (need to order from Kremer)

yellow ochre (in lab)

broom flower

weld

ceruse (order from Kremer)

chalk (in lab)

eggshell (buy from grocery store?)

rabbit skin glue

Materials

glass muller and glass board

1000 ml beakers

filters

thermometers

pipette

glass board and grinder

paint brushes

test board

Safety

Special protocol for working with massicot and ceruse.

Trials

Yellow Ochre

From Cennini: Ocher color is of two sorts, light and dark. Each color calls for the same method of working up with clear water; and work it up thoroughly, for it goes on getting better...And this color is coarse by nature.

- Mix together yellow ochre and water with glass muller on glass board until smooth

- Mix with rabbit skin glue solution (1:15) [from Mariolijn's recipe for red bole]

- paint on board (about 4 layers?--until color is opaque)

- make verdigris

- combine verdigris with yellow ochre (can test varying degrees of yellow)

- paint verdigris and yellow ochre mixed pigment on board

From Cennini: (On a color called giallorino, noted as massicot) This color is to be ground, like the others aforesaid, with clear water. It does not want to be worked up very much, and, since it is very troublesome to reduce it to powder, you will do well to pound it in a bronze mortar, as you have to do with the hematite, before you work it up. And when you have made use of it, it is a very handsome yellow color; for with this color, with other mixtues, as I will show you, attractive foliage and grass colors are made. And as I understand it, this color is actually a mineral, originating in the neighborhood of great volcanoes; so I tell you that it is a color produced artificially, though not by alchemy.

Merrifield, Paduan Manuscript: 121. Straw colour--Take lead yellow (massicot), wash it with a very strong and clean ley, then decant the ley, and distemper with the colour with parchment glue.

- Mix together yellow ochre and water with glass muller on glass board until smooth

- Mix with rabbit skin glue solution (1:15) [from Mariolijn's recipe for red bole]

- paint on board

- make verdigris

- combine verdigris with massicot (can test varying degrees of yellow)

- paint verdigris and massicot mixed pigment on board

<id>p063v_3</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>It is made with the broom flower well boiled in water, putting in it enough alum, then some ceruse.</ab>

</div>

<id>p063v_3</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>Se faict avecq de la <m>fleur de genest<m> fort bouillié<lb/>

dans de l’<m>eau</m>, y mettant suffisament de l’<m>alum</m>, puys<lb/>

Merrifield, Paduan Manuscript can be adapted:

133. To make giallo santo.*--TAke the berries of the buckthorn towards the end of the month of August, boil them with pure water. until the water is loaded and thick with colour; add a little burnt roche alum and then strain it. You may boil the strained liquor to make the colour deeper, mixing with it some very pure gilder's gesso; then make the colour into pellets, and dry them in the shade. *In the Nuovo Plico, Giallo SAnto is said to be made of the flowers of the Erba Lizza, Barbi de Becco (yellow goat's beard). We may, therefore, safely infer that it was a yellow lake made sometimes with the juice of one plant, and sometimes with that of another.

de la <m>ceruse</m>.</ab>

- Make broom flower pigment:

- precipitate onto chalk

- precipitate onto crushed eggshell

- precipitate onto ceruse

- Mix together broom flower scudegrun pigment and oil with glass muller on glass board

- paint on board

- make verdigris

- combine with verdigris with broom flower scudegrun (varying degrees)

- paint on board

<id>p010r_2</id>

<head><m>Stil de grain yellow</m></head>

<ab>It is made in <pl>Lyon</pl> from the <m>sap of weld</m>mixed with <m>chalk</m> or better yet with <m>ceruse</m>, which is appropriate for <m>tempera</m> and <m>oil</m>. </ab>

</div>

<id>p010r_2</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>Il se faict à <pl>Lyon</pl> avecq du <m>suc de gaulde</m> & de la <m>croye</m> incorporée<lb/>

ensemble, ou pour mieulx avecq de la <m>ceruse</m> qui est propre à<lb/>

destrempé et à <m>huile</m>.</ab>

Merrifield, Brussels manuscript can be adapted: 194. To make good and fine arzica Take 1 lb of weld, which the dyers use, cit it very fine, then put it into a glazed or tinned base, and add it to enough water to cover the herb. Make it boil until the water is half wasted, and if there is not enough water add a sufficient quantity and no more; then take 2 oz. travertine (q.v.) finely ground, or 2 oz. white lead, and half oz. of roche alum ground very fine, then put all these things together a little at a time to boil in the vase directly, before the water cools, and stir the water continually, removed the vessel from the fire, and when nearly dry, pour off the water. Then take a new brick hollow in the middle, layer the arzica on it, and let it settle perfectly; then put it on a small and well polished board to dry, and it is done.

From Libro Secondo de Diversi Colori e Sise da Mettere a Oro: A Fifteenth-Century Technical Tretise on Manuscript Illumination, Arie Wallert, The Getty Conservation Institute in Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practices, University of Leiden, 26-29 June 1995

(pg. 41) [21] To make the yellow “arzicha.” Take very well ground eggshells and put them in the hollow of a new brick. Take the weld herb of the textile dyers and let it boil in water with a little bit of alum. Pour it on the eggshells and thus make it as light or as dark and you wish (24).

- Make weld pigment:

- precipitate onto chalk

- precipitate onto eggshell

- precipitate onto ceruse

- Mix together weld scudegrun pigment and oil with glass muller on glass board

- paint on board

- make verdigris

- combine with verdigris with weld scudegrun (varying degrees)

- paint on board

*Several sources (see below) note that colors termed "scudegrun" or "giallo santo" are often made of indeterminate plant bases. The recipes listed here all related a similar process for deriving lake pigment in a way similar to our red lakes reconstruction.

General

- The base of each of these trials will include verdigris and oil (I can experiment with types of oil used). The main variable is (usually yellow) pigment I add.

- I plan to paint each of the different combinations, with varying amounts of the additional pigment, on my test panel first to see resulting difference in shade of green.

- yellow ochre

- massicot

- weld (needs to be prepared before trial, depending on type of weld we source)

- broom flower (needs to be prepared before trial with verdigris)

- In a later trial, paint the most suitable, perhaps judged by color fastness, lack of runniness, time it takes to dry, etc. on metal casts.

- compare resulting color to dyed fabric using the same plant base (primarily weld).

<div>

<id>p158v_1</id>

<head>Colors for green leafs</head>

<ab>One usually paints them with oil colors, because distemper colors do not stay on. For marigold flowers, lightly ground minium for some of them; for more yellowish ones, mix in a bit of massicot. For green, the vert-de-gris is dark and too somber. If it is a yellowish-green, you can mix with the vert-de-gris a bit of yellow ochre and scudegrun. If the green is dark, mix in some coals made from peach pits, which makes a greenish-black, in the same way than the bone of an ox foot bone makes a bluish-black. And in such a manner, by judgement and discretion, put the color on the natural flower or leaf to see whether it is similar to the original. But paint it on very lightly so as not to cover the features of the work.</ab>

</div>

French

<div>

<id>p158v_1</id>

<head>Couleurs pour les feuilles vertes</head>

<ab>On les paint co{mmun}ement à <m>huile</m> pource que les <m>couleurs<lb/>

à destrempe</m> n’ont point de tenue. Pour fleur de soulcy,<lb/>

le <m>minium</m> peu broyé pour aulcuns, & pour d’aultres qui<lb/>

sont plus jaulnastres, un peu de <m>massicot</m> parmy.<lb/>

Pour vert, le <m>vert de gris</m> a fonds & est trop obscur.<lb/>

Si c’est un vert jaulnastre, tu peulx mesler avec<lb/>

le <m>verdegris</m>, un peu d’<m>ocre</m> jaulne & de <m>scudegrun</m>.<lb/>

Si le verd est obscur, mects parmy du <m>charbon<lb/>

de noyau de pescher</m>, qui faict un noir verdastre,<lb/>

co{mm}e le noir d’<m>os</m> de pied de bœuf faict bleuastre.<lb/>

Et ainsy, par jugement & discretion, mects la couleur<lb/>

sur la fleur ou foeille naturelle pour voyr<lb/>

si elle aproche bien. Mays couche la fort clere, pour ne<lb/>

couvrir pas les traicts de l’ouvrage.</ab>

</div>

[Related Recipes]

Recipes related to Yellow<id>p010r_2</id>

<head><m>Stil de grain yellow</m></head>

<ab>It is made in <pl>Lyon</pl> from the <m>sap of weld</m>mixed with <m>chalk</m> or better yet with <m>ceruse</m>, which is appropriate for <m>tempera</m> and <m>oil</m>. </ab>

</div>

<id>p010r_2</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>Il se faict à <pl>Lyon</pl> avecq du <m>suc de gaulde</m> & de la <m>croye</m> incorporée<lb/>

ensemble, ou pour mieulx avecq de la <m>ceruse</m> qui est propre à<lb/>

destrempé et à <m>huile</m>.</ab>

<id>p063v_3</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>It is made with the broom flower well boiled in water, putting in it enough alum, then some ceruse.</ab>

</div>

<id>p063v_3</id>

<head><m>Scudegrun</m></head>

<ab>Se faict avecq de la <m>fleur de genest<m> fort bouillié<lb/>

dans de l’<m>eau</m>, y mettant suffisament de l’<m>alum</m>, puys<lb/>

de la <m>ceruse</m>.</ab>

<id>p063r_4</id>

<head>Shadows</head>

<ab>German <pro>painters</pro> shade their flesh tones with <m>jet</m>, crushed with <m>scudegrun</m> and <m>ochre</m>.</ab>

</div>

<id>p063r_4</id>

<head>Ombres</head>

<ab>Les <pro>painctres</pro> allemans font leurs ombres des carnations<lb/>

des hommes avecq du <m>geyet</m> broyé du <m>scudegrun</m> & de l’<m>ocre</m>.</ab>

<div>

<id>p065r_1</id>

<head>Shadows</head>

<ab> Because blacks produce various colors, some reddish black, others bluish, and others greenish, choose those verging on yellow in order to obtain beautiful shadows in <m>oil</m>, for men’s shadows are similarly yellowish, and for this effect use very strongly crushed <m>[...]</m>, which you mix with a bit of <m>yellow ochre</m> and <m>white lead</m>, that is after you have crushed your <m>white lead</m> and gathered with the <figure/> crushed with the <m>[...]</m>. This way it <sup>the black</sup> will be more desiccative, and on its own producing a yellowish black, when mixed with a bit of white it will be perfect for men’s shadows. Blacks which produce a greenish black are appropriate for women’s shadows. Take then some black of <figure/>, a little <m>sap green</m> and some <m>bistre</m>, and you will have a perfect woman’s shadow in distemper.</ab>

<id>p062r_2</id>

<head><m>Ochre</m></head>

<ab>Apply some on the face, the hair, the heads of dead people and rocks.</ab>

</div>

<div>

<id>p059v_4</id>

<head>Dessicatives</head>

<ab><m>White lead</m> and <m>massicot</m> are the most dessicatives they need though at least two days. If you want to check if some <m>oil</m> is desiccative, mingle it with some <m>white lead</m> and if a crust appears quickly that means that it will dry.</ab></div>

<div>

<id>p065r_4</id>

<head>Greasy colors</head>

<ab>After the laid-down colors are absorbed, if some part remains shiny and does not seem dry, it means that this part is greasy, and that the second colors you lay down will not adhere […] if you do not scrub this part with <m>soap</m> or breathe on it because humidity will make the colors adhere.</ab>

<note>

<margin>left-bottom</margin>

All greasy colors, like <m>ceruse</m>, <m>minium</m>, <m>massicot</m>, <m>ocher</m>, <m>white lead</m> are good for making a <m>gold</m> color.</note>

Cennino Cennini on Yellow

ON THE CHARACTER OF A YELLOW COLOR CALLED OCHER. CHAPTER XLV

A natural color known as ocher is yellow. This color is found in the earth in the mountains, where there are found certain seams resembling sulphur; and where these seams are, there is found sinoper, and terre-verte and other kinds of color. I found this when I was guided one day by Andrea Cennini, my father, who led me through the territory of Colle de Val d'Elsa, close to the borders of Casole, at the beginning of the forest of the commune of Colle, above a township called Dometaria. And upon reaching a little valley, a very wild steep place, scraping the steep with a spade, I beheld seams of many kinds of color: ocher, dark and light sinoper, blue, and white; and this I held the greatest wonder in the world--that white could exist in a seam of earth; advising you that I made a trial of this white, and found it fat, unfit for flesh color. In this place there was also a seam of black color. And these colors showed up in this earth just the way of a wrinkle shows in the face of a man or woman.

To go back to the ocher color, I picked out the "wrinkle" of this color with a penknife; and I do assure you that I never tried a handsomer, more perfect ocher color. It did not come out so light as giallorino; a little bit darker; but for hair, and for costumes, as I shall teach you later, I never found a better color than this. Ocher color is of two sorts, light and dark. Each color calls for the same method of working up with clear water; and work it up thoroughly, for it goes on getting better. And know that this ocher is an all-round color, especially for work in a fresco; for it is used, with other mixtures, as I shall explain to you, for flesh colors, for draperies, for painted mountains, and buildings and horses, and in general for many purposes. And this color is coarse by nature.

ON THE CHARACTER OF A YELLOW CALLED SAFFRON. CHAPTER XLVIIII

A color which is made from a herb called saffron is yellow. You should put it on a linen cloth, over a hot stone or brick. Then take half a goblet or glass full of good strong lye. Put this saffron in it; work it up on a slab. This makes a fine color for dyeing linen or cloth. It is good on parchment. And see that is is not exposed to the air, for it soon loses its color. And if you want to make the Most perfect grass color imaginable, take a little verdigris and some saffron that is, of the three parts let one be saffron; and it comes out the most perfect grass-green imaginable, tempered with a little size, as I will show you later.

ON THE CHARACTER OF A YELLOW COLOR CALLED GIALLORINO.* CHAPTER XLVI

A color known as giallorino is yellow, and it is a manufactured one. It is very solid, and heavy as a stone, and hard to break up. This color is used in fresco, and lasts forever, that is, on the wall; and on panel, with temperas. This color is to be ground, like the others aforesaid, with clear water. It does not want to be worked up very much, and, since it is very troublesome to reduce it to powder, you will do well to pound it in a bronze mortar, as you have to do with the hematite, before you work it up. And when you have made use of it, it is a very handsome yellow color; for with this color, with other mixtues, as I will show you, attractive foliage and grass colors are made. And as I understand it, this color is actually a mineral, originating in the neighborhood of great volcanoes; so I tell you that it is a color produced artificially, though not by alchemy.

*The identification of this color must be attempted in a future study. For practical purposes, massicot, a yellow oxide of lead, prepared by roasting white lead, may be employed. Natural massicot, of volcanic origin, is know; but it is not generally available.

THE WAY TO PAINT TREES AND PLANTS AND FOLIAGE, IN FRESCO AND iN SECCO. CHAPTER LXXXVI

...Then make up a green with giallorino, so that it is a little lighter, and do a smaller number of leaves, starting to go back to shape up some of the ridges. Then touch in the high lights on the ridges with straight giallorino, and you will see the reliefs of the trees and of the foliage.

HOW YOU SHOULD TINT PAPERS GREENISH GRAY, OR DRAB. CHAPTER XXII

You will make a greenish gray, or drab, in this manner. First take a quarter of an ounce of coarse white lead; the size of a bean of light ocher; less than half a bean of black. Grind these things well together in the regular way. Temper as I have taught you for the others, always putting in, for each batch, at least as much as a bean of calcined bone. And this must suffice you for papers tinted in various ways.

Merrifield, Yellow

PADUAN MANUSCRIPT (pg. 648)

Yellow is made with "gialdolino de fornace" of Flanders and Germany,*orpiment, and ochre, with saffron and gamboge for water-colour painting. * In Haydocke's translation of Lomazzo, written in 190, the names of these two colours are translated "Masticot" and "generall."

(pg. 650)

Yellow is made with white lead and gialdo santo.

(pg. 694)

101. Yellow--Socotrine aloes distempered with clear water. Dry buckthorn berries, pounded finely with pulverized saffron, are boiled with alum water until the water is reduced to two-thirds; it is then strained and dried in the sun. The quantities may be caried at pleasure.

(pg. 704) MINIUM

119. To prepare minium.--Take the minium, steep it in water, beat it up well; then decant the finest part, and let it dry. It is to be incorporated with parchment size and a little purified honey.

(pg. 704)

121. Straw colour--Take lead yellow (massicot), wash it with a very strong and clean ley, then decant the ley, and distemper with the colour with parchment glue.

(pg. 708)

133. To make giallo santo.*--TAke the berries of the buckthorn towards the end of the month of August, boil them with pure water. until the water is loaded and thick with colour; add a little burnt roche alum and then strain it. You may boil the strained liquor to make the colour deeper, mixing with it some very pure gilder's gesso; then make the colour into pellets, and dry them in the shade. *In the Nuovo Plico, Giallo SAnto is said to be made of the flowers of the Erba Lizza, Barbi de Becco (yellow goat's beard). We may, therefore, safely infer that it was a yellow lake made sometimes with the juice of one plant, and sometimes with that of another.

BRUSSELS MANUSCRIPT (Merrifield, pg. 786)

...saffron, which is mixed with massicot, pale yellow, golden gellow, brown minium and "cendres," and the colour of dead leaves, sap-green, calcined [vitriol?] "du mourant;" sea-green and "du gay," saffron, green-yellow made from the berries of the buckthron; distilled verdigris [?], green-blue and mountain-blue, terre verte...I omit several other colours which are distilled and obtained from minerals and metals, as well as those used with oil, the different mixtures of which would fill a whole book.

194. To make good and fine arzica Take 1 lb of weld, which the dyers use, cit it very fine, then put it into a glazed or tinned base, and add it to enough water to cover the herb. Make it boil until the water is half wasted, and if there is not enough water add a sufficient quantity and no more; then take 2 oz. travertine (q.v.) finely ground, or 2 oz. white lead, and half oz. of roche alum ground very fine, then put all these things together a little at a time to boil in the vase directly, before the water cools, and stir the water continually, removed the vessel from the fire, and when nearly dry, pour off the water. Then take a new brick hollow in the middle, layer the arzica on it, and let it settle perfectly; then put it on a small and well polished board to dry, and it is done.

From Pigment compendium: The Bolognese MS actually uses the term gualda, which was a Spanish and Portuguese name for Reseda luteola; this in turn was also known to Spanish painters as ancorca (q.v.) or encorca and, when used for estofado painting, was mixed with lemon juice and a weak glue size...The Italian term Giallo santo (q.v.) refers to a yellow lake colour of indeterminate source which could have been weld. (pg. 394-395)

From Libro Secondo de Diversi Colori e Sise da Mettere a Oro: A Fifteenth-Century Technical Tretise on Manuscript Illumination, Arie Wallert, The Getty Conservation Institute in Historical Painting Techniques, Materials, and Studio Practices, University of Leiden, 26-29 June 1995

(pg. 41) [21] To make the yellow “arzicha.” Take very well ground eggshells and put them in the hollow of a new brick. Take the weld herb of the textile dyers and let it boil in water with a little bit of alum. Pour it on the eggshells and thus make it as light or as dark and you wish (24).

COLOURS USED IN PAINTING--YELLOW PIGMENTS

Arizica--Two pigments are know by this name in medieval MSS.

The first kind of arizca is mentioned by Cennini (cap. 50), who says it was much used at Florence for miniature painting. With regard to the nature of the pigment, he observes merely that it is an artificial colour. The Bolognese MS., written about the time of Cennini, or soon after, proves that it was a yellow lake made from the herb "gualda," which is the Spanish and Provencal name for the Reseda luteola. The plant has been used as a yellow dye not only in England but in all Europe, from a very early period. This yellow lake was known to the Spanish painters under the name of ancorca or encorca, and when used for the kind of painting called "estofado," was mixed with lemon juice and weak size.

The second kind of arizica is stated to be a yellow earth for painting, of which the mounds for casting brass are formed. A yellow loam is still used for this purpose in the foundries at Brighton. It is brought by sea from Woolwich, and when washed and dried it yields an ochreous pigment of a pale yellow colour. When burnt it changes to an orange colour, which is likely to prove valuable in painting…

Auripigmentum or Oripiment.---There was a native as well as an artificial pigment known by this name. The former is found in masses in the neighbourhood of Naples, and in other volcanic countries. It has the great advantage over the artificial pigment of being less poisonous. The artificial pigment only seems to have been known to Cennini. Being difficult to grind, powdered glass was mixed with it, as we are expressly told, for this purpose. And Pacheco directs that oripiment should be mixed with linseed oil, made drying by boiling it with red lead or copperas in powder. For miniature painting it was tempered with gum-water and white of egg. Its brilliant yellow colour renders it a desirable pigment for draperies in oil painting, but it is not durable when mixed with oil, and dries very slowly. The author of the third book of Eraclius says, "If you mix oil with it, it will never dry." Lebrun remarkss, that "fat oil should be added to oripiment or make it dry, otherwise it will never dry"...

(pg. clxiv) The French called pigments of this description "stil de grain," and include under them not only those pigments which are of a pure yellow colour, but such as incline to green. The English term for this class of pigments is or was "pink." Thus we have "Dutch pink," "Italian pink" "brown pink," etc.

(pg. clxv) Saffron, zafferano, the crocus of the middle ages, is produced from the flowers of the crocus. Peter de S. Audemar informs us that saffron was produced in France in his time; but he says the French saffron was not good; he mentions that this drug was imported from Spain and Italy, and that the best kind was brought from Sicily, and was called corsicos. The plant is cultivated extensively in England in the neighbourhood of Saffron-Walden, and the name of the place is derived from this circumstance...

Pigment Glossary, Jo Kirby

Earth, yellow (Spreus okker, terra gialla): Yellow to brown iron oxide pigments, deriving their colour from goethite (a-FeOOH) or a similar mineral; clay minerals and quartz are also often present. Although these pigments occur very widely, certain regions, including France and central Italy, were the source of yellow ochres of particularly good colour so that yellow ochre is found a an item of international trade.

(pg. 453) Ochre, yellow (Egergelb (colloquial), gelber Ogar, hockers (chores in general), ochrae vulgar, ocker gel, ocker gelb, ocre de rux, ocria, Ogergelb, oker de Luke, oker de rowse, spreus okker, sprewse oker, terra gialla): Yellow or brownish-yellow iron oxide pigments, deriving their colour from goethite (a-FeOOH) or a similar mineral. Some regions, notably central Italy and France, were the source of ochres of a particularly good, bright yellow colour. The origin of the name oker de Luke is uncertain, although both Lucca (Italy) and Liege (Luik in Dutch) have been suggested; oker de rowse or de rux, which seems to have been a brownish-yellow, is similarly obscure, Spruce ochre (Spreus okker) is a dull brownish-yellow earth found near Oxford (UK), the name deriving from ‘Prussia’ from where, in the past, a similar pigment was presumably once obtained.

(pg. 452) Lake, yellow (Ancorca, arzica, azicha, giallo santo, pincke, pynch, pynke, scheijtgeel, Schietgelb, schijtgeel, Schitt Gelb, Schuttgelb, Spinzerbino): Yellow translucent pigment made by precipitating a yellow dye extracted from a plant source onto a suitable substrate, commonly calcium-containing, but other white materials and also hydrated alumina could be used. The plan sources used included those impotant for dyeing: weld, Reseda luteola L. and dyer’s broom, Genista tinctoria L., which grew all over Europe. The unripe berries from several species of buckthorn were also used, including the common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica L., spincervino in Italian), found over most of Europe. These gave warmer yellows than the rather acid yellows given by weld and broom. Other local plants could easily have been used: many plants give yellow dyes. In all languages, the names of yellow lakes rarely give any clue as to the dyestuff content. Some names (perhaps Schuttgelb, Schietgelb and variants) may relate to the pharmacological prperties of the purgative Rhamnus berries (and the Dutch schijtgeel is also thought to refer to the colour, resembling excrement); the etymology of the English pincke, pynke and other spellings is unknown. Arzica is said to be a corruption of the Greek arsenicon, oripiment, referring to a non-poisonous substitute of similar colour.

(pg. 448) Dyer’s broom: Genista tinctoria L., the source of a yellow dye, obtained from all parts of the plant except the roots. The dye was used in the preparation of rather acid lemon to brownish-yellow lake pigments, very similar to those made from weld (q.v.). The plant was found all over Europe.

(pg. 458) Weld: Reseda luteola L., source of the most important and widely used yellow dye, found all over Europe. The whole of the plant is used, apart from the root. Used in the preparation of yellow lake pigments, giving rather acid lemon to brownish yellows.

Pigment Compendium

WELD--Weld is a dyestuff derived from Reseda luteola (‘dyer’s rocket’, ‘dyer’s herb’, ‘fuller’s herb’ or ‘weld’) of which the principal colouring matter is the yellow flavonoid compound luteolin (q.v.). It was the most universally used yellow dye in mediaeval Europe prior to the widespread availability of quercitron (q.v.), and although it has less colouring power than some other yellow dyes, it is desirable as it produces a very pure colour (gettens and Stout, 1966) said to be as brilliant as oripiment. The pigment is produced by strewing the whole dried plant in a weak solution of alum and then precipitating this with the addition of calcium sulfate, eggshell or lead white. Thompson (1960) states that the colour was most beautiful when somewhat opaque but that when precipitated onto eggshells or lead white it produced a very brilliant colour…

From http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/research/meaning-of-making/vermeer-and-technique/vermeers-palette#yellowlake

Prepared by the precipitation or adsorption of an organic dyestuff onto an insoluble substrate. A common source for yellow dyestuff was the weld plant. The simplest and most direct method used to extract the dyestuff from the raw material was with water or an alkali. The alkali, or lye, was commonly prepared from the ash of wood or other plants extracted with water. The soluble dyestuff components were then converted into the insoluble lake pigment by the addition of alum (potassium aluminium sulphate) and often in the case of yellow lakes, some form of calcium carbonate such as chalk. In fact, analyses of yellow lakes in 17th-century paintings have shown that they almost always contain predominantly chalk.

[Ceruse]

<div>

<id>p065v_5</id>

<head><m>Lead white</m></head>

<ab>It does not fade and has a lot of body.</ab>

</div>

The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Arts

(pg. 510-511) Lead white (white lead, flake white, Cremnitz white, silver white, ceruse) is chemically the basic carbonate of lead (2PbCO3.Pb(OH)2). Although this compound occurs naturally as the rare mineral hydro-cerusite, the pigment has been prepared artificially since early times...

Merrifield

(pg. 23) Cerusa: est color albus qui fit de plumbo; aliter vocatur bracha seu blacha, et aliter glaucus et alibi dicitur que cerusa fit de cupro adusto.

(pg. 156) Manuscripts of Jehan le Begue 197. How and with what vehicles to temper colours for painting in books.--When mixing colours for painting in books, make a vehicle of the clearest gum arabic and water, as before, and mix with it all colours except green and ceruse, minium, and carmine. Salt green is of no use in a book. Spanish green you must temper with wine, and if you wish to shade it, add a little of the juice of sword grass, or cabbage, or leek. You must mix minium and ceruse, and carminium, with white of egg. Grind azure with soap, and wash it, and mix it with white of egg.

(pg. 234) Manuscripts of Jean le Begue XXXVI. How ceruse is made, and how red minium is made from that.--If you wish to make red minium, or the white which is called ceruse, take lead plates, and put them into a new jar, and so fill the jar with very strong vinegar, and cover it up and set it in some warm place, and leave it for a month. Then open the jar, and put what you find adhering to the slips of lead into another jar, and place it upon the fire, and keep stirring up the colour until it becomes white as snow. Then remove it from the fire, and take as much as you like of that colour, which is called ceruse. Put the rest back over the fire, and keep stirring it, because, if it is not stirred, it turns back again to white lead. Then take it from the fire and let the jar cool.

(pg. 314) Manuscripts of Jehan le Begue 343. The nature and condition of minium, sandaraca, and ceruse, and the way to distemper them.--They are all of the same kind and nature, but when exposed to heat they change their name, strength, and colour; for that which is the most heated is the reddest, and that which is the least heated is the whitest or palest, and they should be distempered with water for mason's work, with egg for parchment, and with oil for wood.

(pg. 774) Brussels Manuscript 17. Ceruse is made of lead and vinegar; it is good in the flesh colour and similar things. Burnt ivory, which was used bu Appelles, is a most excellent black, for if it is dissolved in vinegar and dried in the sun it cannot be effaced. There are some works of powerful colouring, others feeble; the latter, after the first painting, must be heightened with vigorous colours.\

Pigment Glossary, Jo Kirby

(pg. 447) Ceruse (cerussa, cyreus, serruys): usually a variety of lead white (q.v.). Some authorities, particularly in the late 16th and early 17th century, describe it as a mixture of lead white and chalk; others use it as a synonym, or to indicate a high grade of lead white.

Recipes related to Green

<div>

<id>p063v_5</id>

<head> Flanders blue-green </head>

<ab>In the month of May, one puts some putrified cow dung under horse dung. Then mix them with iron.</ab>

</div>

<div>

<id>p073r_1</id>

<head>For making <m>blue florey</m> varnish or <pl>Flanders</pl> <sup>varnish</sup></head>

<ab>Take the <m>blue florey</m> and <m>quicklime</m>, and put on around four fingers' worth of <m>water</m> and leave it to soak for one day. Take the <m>water</m> where the aforesaid <m>quickline</m> has soaked, and put your <m>blue <sup>florey</sup></m> with it, and put it on the <m>wood</m>.</ab>

</div>

<id>p063r_6</id>

head><m>Verdigris</m> and other very beautiful gray green</head>

<ab>One must not grind it only with <m>water</m>, because this makes it fade. To obtain a beautiful distemper, some people crush it with <m>vinegar</m>. But this makes it turn pale and become whitish. To make it beautiful, crush it with <m>urine</m> and leave it to dry. Then, when you will want, crush it with <m>oil</m>. And after you have collected it with the palette, instead of finishing cleaning the <m>marble</m>, crush it there with <m>scudegrun</m> and you will have a very beautiful green.</ab>

</div>

<id>p039r_2</id>

<head><m>Dyers woad</m></head>

<ab>It is grown in <pl>Auragnes</pl> where the soil is so fertile that if you grew wheat there

every year, it would fall over from the kernels being too full. This is why <m>dyers woad</m>

and wheat are cultivated alternately. For cultivating </m>dyers woad</m>, the soil is ploughed

with <m>iron</m> shovels like those of gardeners. Then with rakes, clods of earth are broken

up and tilled as for the sowing of some vegetable gardens. It is usually sowed on Saint

Anthony’s day in January. Eight harvests can be made. The first ones are the best. The best of

Auragne’s <m>dyers woad</m> is the one from <pl>Carmail</pl> and the one from

<pl>Auraigne</pl>. And sometimes the <m>dyers woad</m> is good in one field and worthless

in another that is closeby. The quality of the <m>dyers woad</m> can be recognized when you

put it in your mouth and it tastes like vinegar, or when you crumble and break it, there are silver

or golden moldlike veins. It is pressed in the dyers’ cistern, and to fill a cistern, six bales are

needed. Several <m>wool</m> flocks are kept there. And if it produces 15 dyings, it is said to

be worth 15 florins, if it produces 20 dyings, 20 florins. The good kind will dye up to 30 times and

usually up to 25 or 26.</ab>

</div>

<title id=”p044r_a5”>Dyes from flowers</title>

<ab id=”p044r_b5”>Red poppies that grow amongst wheat make a very beautiful columbine on

white leather. The boufain makes a very beautiful blue. An herb which grows in hedges,

which has a stem similar to flax, long and broad leaves like little bugloss, which has a

violet flower verging on blue and looks like the fleur de lys, makes a quite beautiful turquin,

better than azure. Another columbine flower of the shape and size of the bugloss flower,

which has a leaf like that of the pansy, also makes a very beautiful turquin. It grows in wheat

in light earth.</ab>

Cennino Cennini on Green

ON THE CHARACTER OF A GREEN CALLED VERDIGRIS. CHAPTER LVI

A color known as verdigris is green. It is very green by itself. And it is manufactured by alchemy, from copper and vinegar. This color is good on panel, tempered with size. Take care never to get it near any white lead, for they are mortal enemies in every respect. Work it up with vinegar, which it retains in accordance with its nature. And if you wish to make a most perfect green for grass..., it is beautiful to the eye, but it does not last. And it is especially good on paper or parchment, tempered with yolk of egg.

Merrifield, Green

(pg. ccxvi) Mineral green pigments, both natural and artificial, are produced from copper. The native green ores of this metal have always been used in painting under the names of mountain green, Hungarian green, chrysocolla, malachite, cenere verde, verde de miniera, verde di Spagna, verdetto, and green bice. To these colours must be added terra verde, which is said by some persons to owe its colour to copper; other consider that it is a bluish or grey coaly clay, combined with yellow oxide of iron or yellow ochre...It was generally considered that mixed green, composed of blue and yellow, were more permanent that any of the before-mentioned green pigments. They were frequently compounded of ultralmarine and oripiment, of azzurro della magna and giallolino, of indigo and orpiment, and of one of the mineral blues with a yellow lake...

Recipes for other colors

<id>p038v_1</id>

<head>Black color for dyeing </head>

<ab>Take <m>lye made from quicklime</m> and <m>white lead</m>, mix and leave to soak

and you will have a dark brown dye, and reiterating the same you will make black. Try other

colours with the <m>lye made of lime</m>.</ab>

<id>p063v_1</id>

<head><m>Velvets</m> and <m>blacks</m></head>

<ab>One must make the main layer very thick, and the folds and highlights of the meste lighten a lot with white and on the ends of its light, you apply a white line. For blue and green velvets, you shade with coal made from peach pits which is very black. Concerning the <m>lacquer</m>, the <m>carbon black</m> that produces a reddish black on lacquer for velvets. The common charcoal produces a whitish black.</ab>

</div>

<id>p038v_2</id>

<head>Against nose bleeding and for dyeing</head>

<ab>Pound some of the kind of “<m>vinete</m>” or “<m>lapathum acutum</m>” that is red-

veined, which is called <m>dragon’s blood</m>, and apply it on the bleeding person’s forehead.

This herb is a strong dye & makes beautiful violet.</ab>

</div>

<title id=”p044r_a5”>Dyes from flowers</title>

<ab id=”p044r_b5”>Red poppies that grow amongst wheat make a very beautiful columbine on

white leather. The boufain makes a very beautiful blue. An herb which grows in hedges,

which has a stem similar to flax, long and broad leaves like little bugloss, which has a

violet flower verging on blue and looks like the fleur de lys, makes a quite beautiful turquin,

better than azure. Another columbine flower of the shape and size of the bugloss flower,

which has a leaf like that of the pansy, also makes a very beautiful turquin. It grows in wheat

in light earth.</ab>

Techniques

<id>p013r_2</id>

<head>To dye</head>

<ab>Mix <m>sal ammoniac</m> and <m>vitriol</m> and boil them together. Then mix in some

<m>laque</m> or <m>vertdegris</m> and <m>azur</m> or similar color, and dye, which will

not come off if the animal does not shed. Non bona.</ab>

Economic Contexts

<title id=“p016v_a3”>Silk</title>

<ab id=“p016v_b3”>Crimson silk is more frequent than all the other ones because its colour is

not as expensive as blue or green ones which are, also, good bargain for the worker. Black

silk is less frequent because it costs a lot.</ab>

fols. 53v-54r: silkworms

<div>

<id>p053v_1</id>

<head><al>Silkworms</al></head>

<ab>They are produced from grain, that is eggs, which are sold by the ounce, which is commonly sold in Languedoc 3 lb. and 5 s. The one from Spain brought by merchants is considered to be the best, because the worms coming from it are not so subject to illnesses and produce more silk. In Spain, one ounce of grain gives worms that commonly make 15 lb. of silk. But from one once produced in France, they do not make but 10 or 12. Three ounces of grain are to produce such a quantity of worms, with which you will be able to furnish a room with three or 4 shelves of wide boards. They begin to shed their skin on their own around Easter. And to do this, one has to put them in a pine box, like the ones in which we put pellet, warmly among feather cushions. And in the beginning, they shed their skin as little black ants, and as soon as there are two or three without skin, they have to be given white mulberry leaves. And then arrange them on the boards. And three times per day, it is necessary to change the leaves for fresh ones. And if during the day there is any storm or rainy weather, cloudy and cool, one needs to keep in the room three or 4 embers and with glowing coal, and to light incense until the room is filled with its smoke. And when the weather is warm and serene, they produce more and better silk. Some worms make it whiter, others more yellowish. And even if it is white, it can be yellowed when it is extracted with hot water. From their birth until the moment they make their cocoons and prisons, worms sleep and rest 4 times, and each time they remain 4 or five days resting without eating, as if they were dying so as to be born again, because each one sheds their skin and begins by uncovering the head, then consequently, on different days, the rest of the body, and they go from white to grey, and from grey to white. And if one of them has some sickness and does not have the strength to shed, one needs to help it and to be careful not to squash it, because if it gives off a yellow liquor, it is no longer worth anything. And they do not even serve much if one handles them. Around Pentecost, they begin to want to climb on the dry heather branches that we prepare and attach

54r

to some of the upper boards, and one can tell when they want to climb up when, on the leaf, they stretch out and raise their heads and a part of their bodies when one takes them to heather branches where they stop and begin to spin their prison, which we call cocoon, generally the size of a pigeon egg, although there are some which are much bigger because it sometimes happens that two or three and up to 11 <al>worms</al> put themselves in a cocoon, which is hairy and cottony, around which ball is filoselle or floret, and of the cocoon, which is a white, solid, continuous and firm skin, <m>silk</m> is made. The cocoon is so hard that it is cut with difficulty with a fingernail. And yet to leave its prison, the <al>worm</al> eats away at it on one end, and after having stayed inside, living on its own juices for three weeks, it comes out, reduced in size by half. Because when it begins to spin, it is as long as a ring finger and has eight legs, and when it comes out it is less than half as long and only has four legs. On the other hand, it has become a butterfly and has wings; however, it does not fly. There are males and females. As soon as they come out of the cocoon, the male mates with the female, and they are put on a piece of white linen where they lay their eggs, which will not be good and viable if the male was not given to her. When the male has detached himself from a female, one must get rid of it because it would not be good to give it to another female. They finish spinning and laying eggs in three weeks and around Saint John’s Day. And then one keeps their eggs and grain until Holy Week, as mentioned. Some [worms] spin among the leaves and make their cocoons there without climbing high.

<id>p038v_6</id>

<head>Crimson</head>

<ab>Because one “aulne” costs seven or eight lb. to dye, they use <sup>cloth</sup>worth

seven or eight francs. But if one wants something beautiful, one should buy some white cloth

worth fifteen francs an “aulne” and dye it with some pure crimson woad & a little cochineal.

Black fabrics are very fine because the dye is inexpensive.</ab>

</div>

NOTES

Links to Modern Websites/Reconstructions of interest

Weld dyeing: http://www.wildcolours.co.uk/html/weld_dyeing.html

Yellow lake: http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/research/meaning-of-making/vermeer-and-technique/vermeers-palette#yellowlake

Broom flower (used in scudegrun) related to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Genista_tinctoria

Possible source for more historical information on yellow: https://salviati.hypotheses.org/918?lang=es_ES

Possible source of natural dye extracts: http://botanicalcolors.com/product-category/natural-dye-extracts/page/2/

--> I talked to her about woad. She does not woad leaves, but has some extracts.

Dyers in the area who might use natural dyes: http://sheepandwool.com/vendors/vendor-list/

Alum used in dyeing, also: http://www.naturalpigments.com/aluminum-sulfate-alum.html

Coal made from peach pits: http://www.fullchisel.com/blog/?p=1501

Woad: http://www.woad.org.uk/html/europe.html

For historic art materials:

http://www.artcons.udel.edu/public-outreach/historic-art-materials/yellow-dyestuffs

From Naomi: Met's Fashion and Virtue - yellow color in textiles: